On Rewriting, Rebuilding, and Turning Toward Mortality

For years now, I’ve been circling the same set of questions, questions that live somewhere between psychology, philosophy, the studio, and the darkroom. Why do humans deny death? What holds our meaning structures together? And why do artists seem to approach these tensions differently than everyone else, often with a kind of clarity that only comes from standing close to fear?

I’ve been asked why In the Shadow of Sun Mountain still isn’t published. The simple truth is that the book outgrew its original frame. I wrote it during a period when I was wrestling with ideas that didn’t yet have the right container. What I couldn’t see then, but can see now, is that the book was waiting for the structure of my doctoral work. It needed a broader foundation, and I needed more time to understand what I was actually trying to say.

So instead of releasing it in its earlier form, I’ve decided to rework it as part of my PhD. It will become the third manuscript in a three-part sequence I’m developing during the program.

The first manuscript will be an explanation of these theories—death anxiety, denial, worldview defense, and the evolutionary roots of awareness—in a way anyone can read and understand. Simple, accessible, and grounded. The working title is Glass Bones.

The second manuscript will be directed toward artists and toward creatives and will explore how they metabolize existential concerns in ways that differ from non-artists. It will look closely at creative practice as a pathway for meaning-making. The working title is Rupture.

And the third will be a rewritten In the Shadow of Sun Mountain, offered as a real-life example of an artist metabolizing these ideas through creative work, reflection, and lived experience.

All of this leads to the question that my dissertation will take up directly:

What actually happens inside an artist when they confront mortality in their creative practice?

To answer that, I’m turning toward arts-based research methodology. ABR is a natural fit for the work I’ve been doing for decades, because in ABR, the studio becomes the site of inquiry. The process becomes a way of knowing. Material becomes a kind of data. Instead of illustrating findings after the fact, the creative act generates them. It’s not about making art that explains theory; it’s about letting the art reveal what theory can’t access on its own.

So the dissertation will center on creating a completely new body of artwork, work made specifically for this research. Clay figures and/or objects suspended or collapsing under their own weight. Wet collodion images that feel like memory rising through fog and confusion. Paintings and photographs that follow the direction of the inquiry. I want the research to grow out of the process itself, out of the contact with clay, with silver, with pigment, with symbol, and with the ambiguous space where meaning forms.

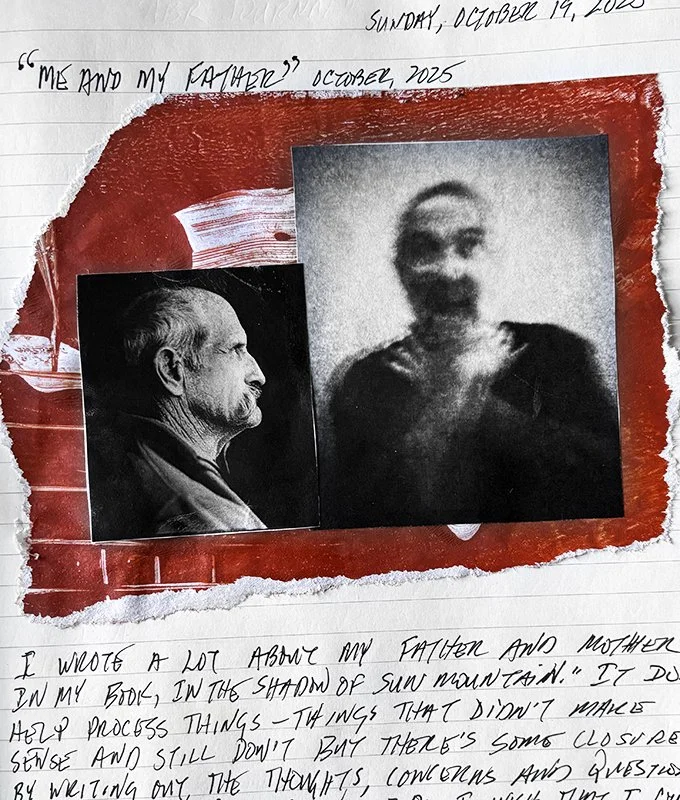

Journal entry - October 2025.

At the same time, I’ll be studying how others respond to this work and what happens psychologically, symbolically, and emotionally when someone encounters artwork that doesn’t look away from mortality. Death denial shows up in recognizable ways: humor, defensiveness, projection, avoidance, and philosophical distancing. But sometimes something deeper appears: recognition, quiet, even a brief moment of meaning.

ABR gives me a structure to study all of this.

My own creative process.

The images that emerge.

The responses they evoke.

The symbolic patterns that repeat.

The ways meaning cracks open or closes down.

It lets me bring the studio, the psyche, and the research questions into one integrated space.

My hope is to create a body of work that matters both inside academia and beyond it. Art isn’t an accessory to life; it’s a method of survival. Artists metabolize things the culture doesn’t know how to hold directly. We take fear, grief, rupture, and turn them into form, into symbols that others can bear to look at. It isn’t therapy and it isn’t escape. It’s a form of existential transformation.

If I can articulate that process, what it feels like, what it reveals, and how it shapes both the maker and the viewer, then the work will have done something meaningful. It will help explain why creative practice is one of the most honest responses we have to our own mortality.

So that’s the direction I’m heading: a reworked Sun Mountain, a sequence of manuscripts that build the conceptual ground, a new exhibition, and a dissertation that uses arts-based research to study the artist’s encounter with mortality from the inside out. I’m building an integrated body of work, creative, philosophical, and experiential, that examines what it means to be mortal and how artists turn that reality into meaning.

More will unfold as the work begins to take shape.