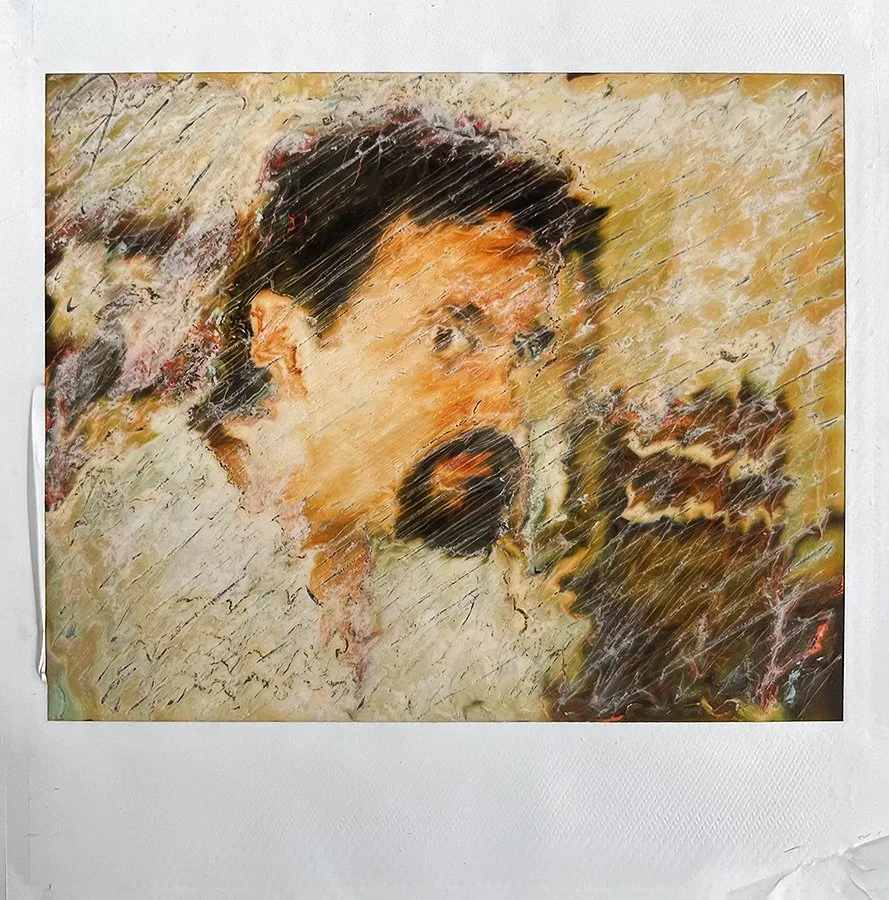

In 1993, I put together a small exhibition called Visions in Mortality. At the time, I didn’t know Ernest Becker’s work, I hadn’t read The Worm at the Core (Terror Management Theory), and Ajit Varki and Danny Brower’s book Denial was still years away from being published. But even without the theory, I knew where my compass pointed. I wanted to make art about death anxiety and existential struggles.

Looking back now, those photographs feel like an instinctive first attempt to break through the evolutionary wall of denial. I didn’t have the language for it then, but what I was doing was confronting the thing most of us spend our lives avoiding. The work wasn’t about distraction or comfort—it was about holding mortality in front of myself and anyone willing to look.

That exhibition planted a seed. It revealed what would become the through-line of my entire practice: how do we live, create, and remain human in full awareness of our impermanence?

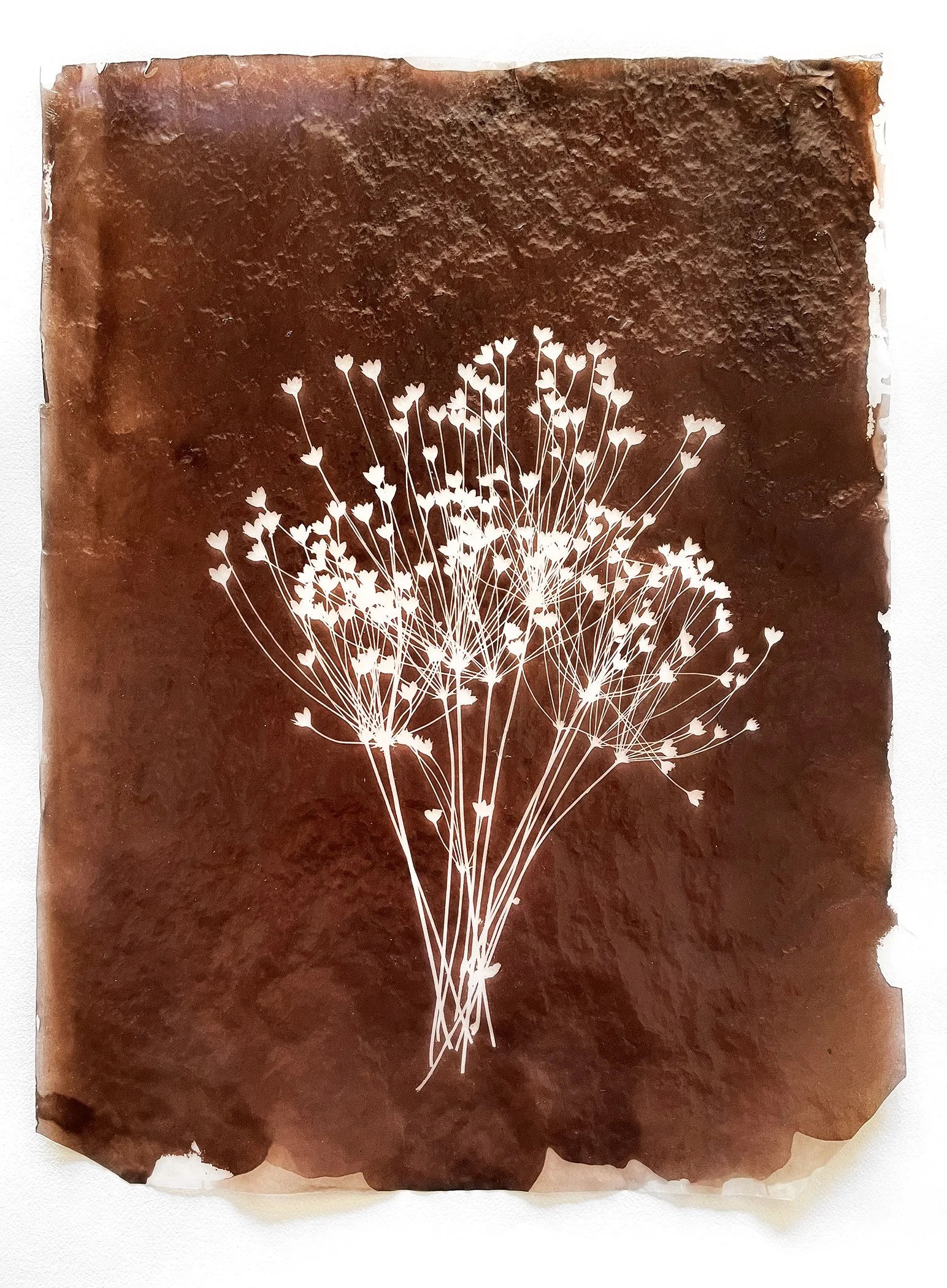

“Gone to Seed,” Whole Plate Photogenic Drawing on vellum paper (waxed). The work was created in 2022 as part of the project titled, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil.”

Three decades later, In the Shadow of Sun Mountain is the mature expression of that same impulse. Where Visions in Mortality was raw, direct, and almost primal, Sun Mountain is layered—woven through with Becker’s insights on cultural worldviews, TMT’s evidence of our defensive psychology, and Varki and Brower’s claim that denial itself had to evolve in order for us to function as conscious beings.

The difference is scope. Visions in Mortality was a solitary confrontation with death, denial, and culture. Sun Mountain is a confrontation with collective denial—the way cultures rewrite history, erase peoples, and commit violence (genocide) in the name of permanence. It’s about how our fear of death doesn’t just haunt us as individuals but shapes entire societies.

But the continuity matters more than the contrast. Both projects spring from the same recognition: that art is one of the few places where denial can falter, where we can face mortality directly without looking away. That has been my practice from the beginning, whether I had the theory to explain it or not.

Now, in my doctoral studies, I’m taking this inquiry a step further. I’m asking not only how artists confront mortality differently than others, but also what that confrontation makes possible—for art, for ethics, and for the way we live together. If Visions in Mortality was the initiation and Sun Mountain the culmination, this research is the extension. It’s an attempt to turn decades of practice into a framework that others—artists, scholars, anyone willing to face the void—can use to think differently about mortality, meaning, and art.

Visions in Mortality was the beginning. Sun Mountain is the continuation. The dissertation will be the next turn in the spiral—returning to the same question from a higher vantage: what does it mean to create, to love, to exist, knowing all along that the universe is indifferent and that everything vanishes?